- Kaci Tavares

- May 20, 2020

- 6 min read

By now, it's safe to say that 2020 has not met any of our expectations. Instead of spending time with family and friends greeting the spring sun, we've been stuck inside commuting from bedroom to living room to kitchen and back again, trying not to get on our housemates' nerves. To fend off impending boredom, many of us have probably turned to our artists: binge-watching that television show that's been in our Netflix watch list forever—in my sad case, ordering knitting needles and learning from YouTube tutorials—or, browsing Goodreads for the next great novel we will definitely read, this time.

I'll be the first to admit, I'm a pro at the whole "buy books to sit on my shelf as I buy more books" lifestyle, and, too often, I use the 24-hour, buy-and-click option that is Amazon Prime. While under lockdown, Amazon Prime might be a lesser evil than breaking social-distancing codes to visit your independent bookstore, but after I learned about the communities and support indie bookstores offer their authors of color (as I spoke about in my last post!), I'm extremely aware of my power as a consumer. You've stuck with me as I've thrown statistic after statistic at you, but now comes a post on the fun part: reading and shopping! Today, I challenge you to consider these two questions:

1. What do you choose to read?

2. Where do choose to get those books from?

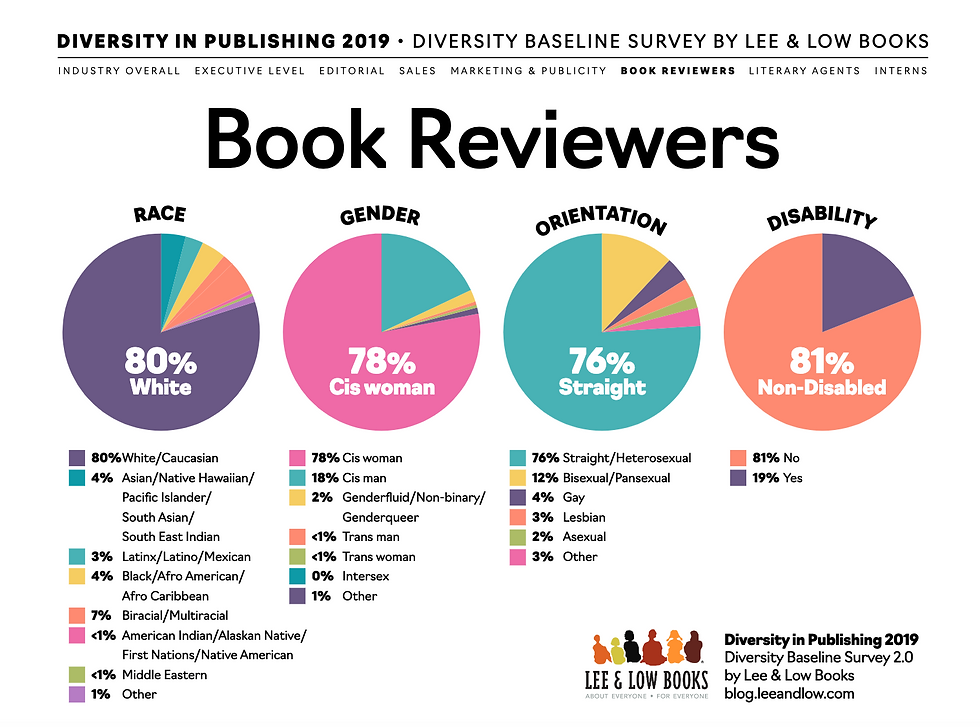

During my research for past posts, I read an interesting article by Sunili Govinnage. An Australian freelance writer, and human rights lawyer, Govinnage was struck by the lack of cultural diversity in the Anglosphere’s book canon. She took a good look at her bookshelves, noticed she was reading mostly books by white, monolingual authors, and decided to make a conscious change to her reading practices. Her experiment? She decided to only read books by minority books for a whole year. Though you can read about her entire experience, here, Govinnage identified many of the systemic problems with the Anglosphere’s publishing industry we’ve already discussed on this blog.

Her first issue was findability. When Govinnage turned to “book reviews, bestseller lists, literary awards, and Amazon.com” (“I read books”), she couldn’t find many books by authors of color to read and decided to ask for suggestions through The Guardian. Though she received many suggestions, she ran into her second problem: accessibility to e-books in the US written by authors from other countries. Though my blog focuses mostly on issues with authors of color being published in the US or UK, Govinnage brings up another important issue: “less than 1 percent of literary fiction and poetry books published in the United States are translations, and more than 60% of those are from Europe and Canada” (Govinnage, “I read books”). These low statistics show just what type of texts the US decides to prioritize translating, or purchasing international rights to. This March, my publishing class and I were supposed to visit the London Book Fair. Understandably, the Fair was cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but as many international rights are negotiated at the Fair, I wonder how many opportunities to color our canon this year were missed?

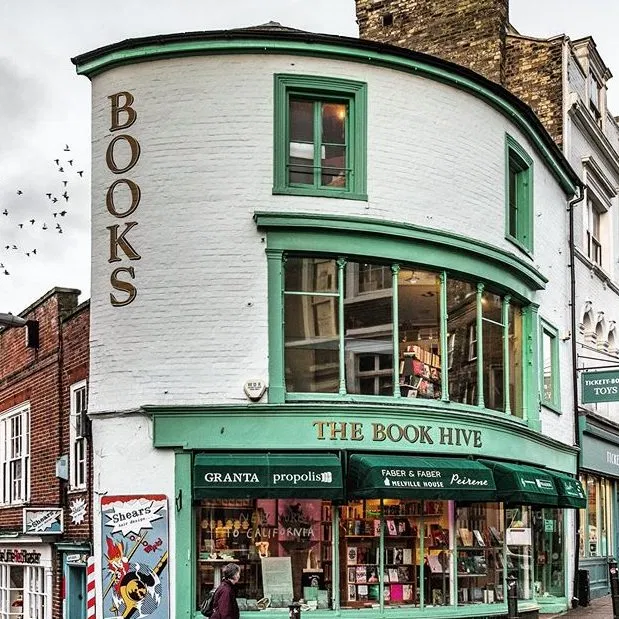

Govinnage experienced similar issues when she tried to purchase books in-person at both independent and large bookstores. In my last post, I discussed how indie bookstores often offer physical spaces for specific readerships to safely gather and develop. These communities grow because of unique seller-customer relationships. Joe Hedinger explains it this way: as The Book Hive’s clientele becomes more diverse, so does its stock to reflect and cater to its growing market (Personal Interview). What we learn here is that indie booksellers pay attention to their customers. As a consumer, it’s worth asking your local bookseller for their book recommendations by minority authors, or if they’ll be willing to stock a specific author for you – they’ll indeed listen to your requests, and you may just see changes in their stock to reflect what you ask for. Don’t ever neglect the power you have as a consumer!

If you don’t have any specific titles you want stocked, by simply choosing to purchase from indie bookstores or directly from small publishers themselves, you are utilizing your power as a consumer. In February, I attended a Carcanet at 50 event. A panel of UK-based, independent poetry publishers pleaded with us to try to purchase through their website directly. Amazon.com, though quick and accessible, offers only 60% commission to publishers on books sold through their website, and that commission can be delayed up to months at a time (Commane, ‘Carcanet at 50 Panel’). Though Amazon offers discount prices, by spending just a bit more and purchasing directly through a publisher’s website, the publisher immediately gets 100% of the profit. And, as we know, purchasing from indie bookstores supports local businesses and the specific, diverse communities within them.

I’ll end with this personal anecdote. To keep busy during quarantine, my mom reorganized our home library. On a FaceTime call, she gave me a virtual tour of our new library, we came across my first claim to authorship: The Mean Cinderella, a retelling of the classic fairy tale I had written in a summer school class when I was nine. For kicks, my mom read out the opening pages to me. While taking a trip down memory lane, I smiled, amused at my overuse of cliché and my poorly-drawn crayon illustrations. It was only later that week, when I was re-watching Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk “The Danger of the Single Story,” that I realized I had drawn my Cinderella and her stepsister as white girls with fair skin, blue eyes, and blonde hair. As a nine year old Chinese-American girl, I had not even considered main character could have my dark brown eyes and straight brown hair. And, as a twenty-three year old woman, I did not find sadness in my choice until I was reminded by another author of colour.

The Mean Cinderella was an important reminder to me that book culture is something that is taught to us as kids in school, and is perpetuated by what books and media we choose to surround ourselves with as adults. I hope after reading this post you are aware of both what you choose to read, and where you choose to get those books from. I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again: we are all part of the positive feedback loop that creates the Anglosphere’s book culture, and we can do our part to help diversity it, and normalize that diversification of it, even as consumers.

Source: amazon.co.uk

I’ve just received Raymond Antrobus’s The Perseverance, Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, and Cathy Park Hong's Minor Feelings: A Reckoning on Race and the Asian Condition. Like Sunili Govinnage, I’m going to try and expand on my own reading choices, and read outside of the cultures I most identify with. Even as a person of color, I realize I need to do a better job of expanding my own reading choices to include all cultures and minority experiences. I’m excited to crack open these spines start that process, and I hope you’ll join me and help do you part to color the canon.

Stay healthy, and keep reading!

Kaci

P.S.

If you'd like some inspiration on where to start, below are the books Sunili Govinnage read during her 2014 experiment. You can also always check out my "Book Recommendations" page on the blog that I'll continue to add to!

Books Read by Sunili Govinnage

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Throne of the Crescent Moon by Saladin Ahmed

Another Country by James Baldwin

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

Foreign Soil by Maxine Beneba Clarke

Open City by Teju Cole

Saree by Su Dharmapala

Tiddas by Anita Heiss

Manhattan Dreaming by Anita Heiss

Paris Dreaming by Anita Heiss

The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez

Butterfly Song by Terri Janke

The Disappearance of Ember Crow by Ambelin Kwaymullina

The Interrogation of Ashala Wolf by Ambelin Kwaymullina

The Lowland by Jhumpa Lahiri

Supernova by Dewi Lestari

The Astrologer's Daughter by Rebecca Lim

Twilight in Jakarta by Mochtar Lubis

Mullumbimby by Melissa Lucashenko

Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor

Here Come the Dogs by Omar Musa

Works Cited

Commane, Jane, panellist. Panel discussion. Carcanet at 50, 25 Jan. 2020, Dragon Hall, The National Centre for Writing, Norwich, UK.

Govinnage, Sunili. "I read books by only minority authors for a year. It showed me just how white our reading world is." Washington Post, 24 Apr. 2015. washingtonpost.com/gdpr-consent/?next_url=https%3a%2f%2fwww.washingtonpost.com%2fposteverything%2fwp%2f2015%2f04%2f24%2fi-only-read-books-by-minority-authors-for-a-year-it-showed-me-just-how-white-our-reading-world-is%2f. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Hedinger, Joe. Personal Interview. 27 Apr. 2020.